Savor Life’s Pleasures, and Improve Your Health at the Same Time?

Hedonism often gets a bad rap. But upon taking a closer look at what hedonism actually is (and is not), you may be surprised that it’s poor reputation is unwarranted. In fact, “rational hedonism” is closely linked to health and wellness. Today we’re posting an excerpt from an article originally posted on TheConversation.com that takes a deep dive into hedonism and how it affects well-being.

I think I might be a hedonist.

Are you imagining me snorting cocaine through $100 notes, a glass of champagne in one hand, the other fondling a stranger’s firm thigh? Before you judge me harshly, I know hedonism has a bad reputation, but it might be time to reconsider.

What if, instead of a guaranteed one-way road to ruin, hedonism is good for your health? If we think of hedonism as the intentional savoring of simple pleasures – like playing in fallen leaves, moments of connection with friends, or cuddling the dog – then it probably is. Seeking and maximizing these kinds of pleasures can boost our health and well-being.

So where do our ideas of hedonism come from and how can we harness hedonism to improve our health and quality of life?

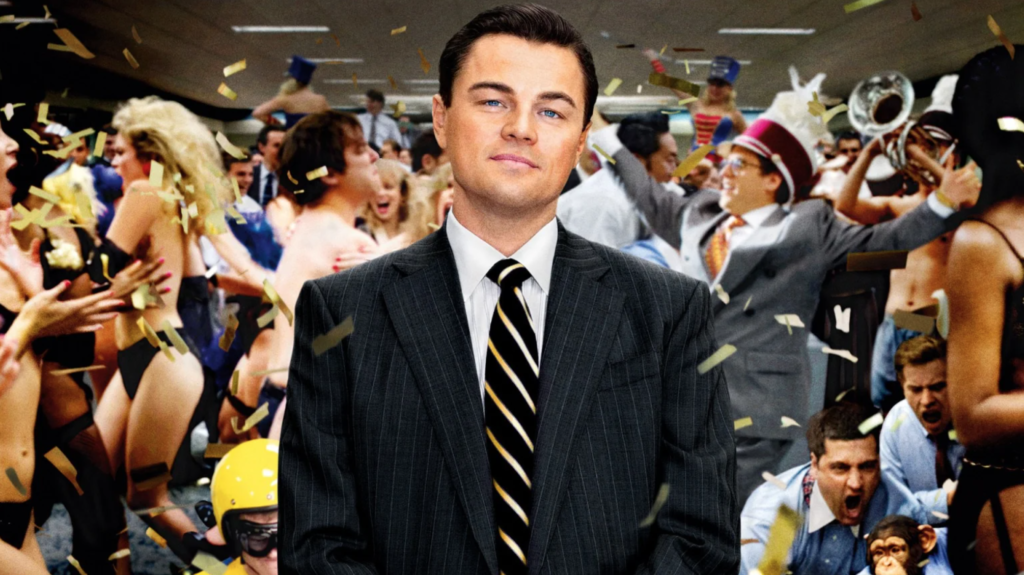

In broad terms, a hedonist is someone who tries to maximize pleasure and minimize pain. Jordan Belfort (played by Leonardo DiCaprio) in The Wolf of Wall Street is probably the popular idea of the quintessential hedonist, where his extreme wealth allows him to indulge his insatiable hunger for all things pleasurable.

But this kind of behaviour is better termed debauchery – extreme indulgence in bodily pleasures and especially sexual pleasures – rather than hedonism.

Hedonism has its philosophical roots as far back as Plato and Socrates, but ancient Greek philosopher Epicurus is often credited with articulating an early brand of hedonism based not on a life of untamed appetites, but on moderate pleasures and respect for others.

If you close your eyes and think about a time you experienced a tingle of pleasure, chances are you’re remembering a sexual experience, or something delicious you’ve eaten. Perhaps the memory is of a very good glass of wine, or those last 50 meters of a long, satisfying run.

Well, these activities are good … until they’re not. Many of the things that commonly give us pleasure can also be used in risky or harmful ways.

It can be difficult to pin down the point at which a previously pleasurable behaviour becomes problematic. But, somewhere between enjoying an occasional beer and needing a drink before getting out of bed each morning, we’ve passed the tipping point.

At this stage though, pleasure is no longer the motivation, nor the result, of the behaviour. The uncontrollable “hunger” has wiped the pleasure away and the best we can hope for is relief. Without pleasure, the behaviour is no longer a hedonic one.

The single-minded pursuit of one intense pleasure at the expense of other aspects of life that bring meaning and pleasure is also counterproductive to living a rich and enjoyable life. This puts it well outside Epicurus’ idea of moderate pleasures and self-control.

So what might a modern hedonist’s life look like?

A practical definition might be someone who tries to maximise the everyday pleasures while still balancing other concerns. I’ll call this a kind of “rational hedonism”. In fact, Epicurus emphasised a simple, harmonious life without the pursuit of riches or glory.

Maximising pleasure, unlike with debauchery or addiction, need not take the form of more, bigger, better. Instead, we savour everyday pleasures. We relish them while they’re happening, using all our senses and attention, actively anticipate them, and reflect on them in an immersive way.

The act of savouring intensifies the pleasure we extract from simple things and delivers greater satisfaction from them. One study found that spending a little time savouring the anticipation before eating chocolate led participants to eat less chocolate overall. And attention seems to be key to the link between pleasurable feelings and well-being.

A state of pleasure is linked with reducing stress. So when we feel pleasure, our sympathetic nervous system – that fight or flight response we experience when we feel threatened – is calmed.

Studies show pleasurable emotions are associated with broader and more creative thinking, and a range of positive outcomes including better resilience, social connectedness, well-being, physical health, and longevity. So, pleasure might not only help us to live more enjoyably, but longer.

Promoting well-being in older adults is a particularly promising area. Savouring pleasure is linked to resilience in older adults and positive emotions can help to offset the ill-effects of loneliness. Plus, regardless of physical health status, the ability to savour is associated with higher levels of satisfaction with life.

And savouring can be taught. One study, looked at the effects of an eight week program promoting savouring for a group of community dwelling adults aged 60 and above. The program reduced depression scores, physical symptoms and sleep problems, and increased psychological well-being and satisfaction with life.

In the meantime, we should defiantly shake off the idea that pleasure is slightly shameful or frivolous and become early adopters of this rational kind of hedonism. We can think of Epicurus, and intentionally savour the simple pleasures we have learned to overlook.

What are the simple pleasures you savor in your life? Let us know in the Comment section below.

I have a problem with the conception of debauchery as perceived in this article. The key word is “excessive”. Who is the judge? If sexual pleasures, the mix of hormones in our blood is the key factor. What is “excessive” for one person is “not enough” for another? Evolution and its creation of infinite diversity regulate everything. Just look at animals enjoying stretching in the sun. Pure hedonism. As long as we follow evolution rather than artificial dictatorial commands of our institutions (religion, state, custom, etc) we are simply OK. With some sarcasm, I am trying every day to be more and more like animals and less and less a human. Life is too short not to partake in all we can from all pleasures the planet supports.